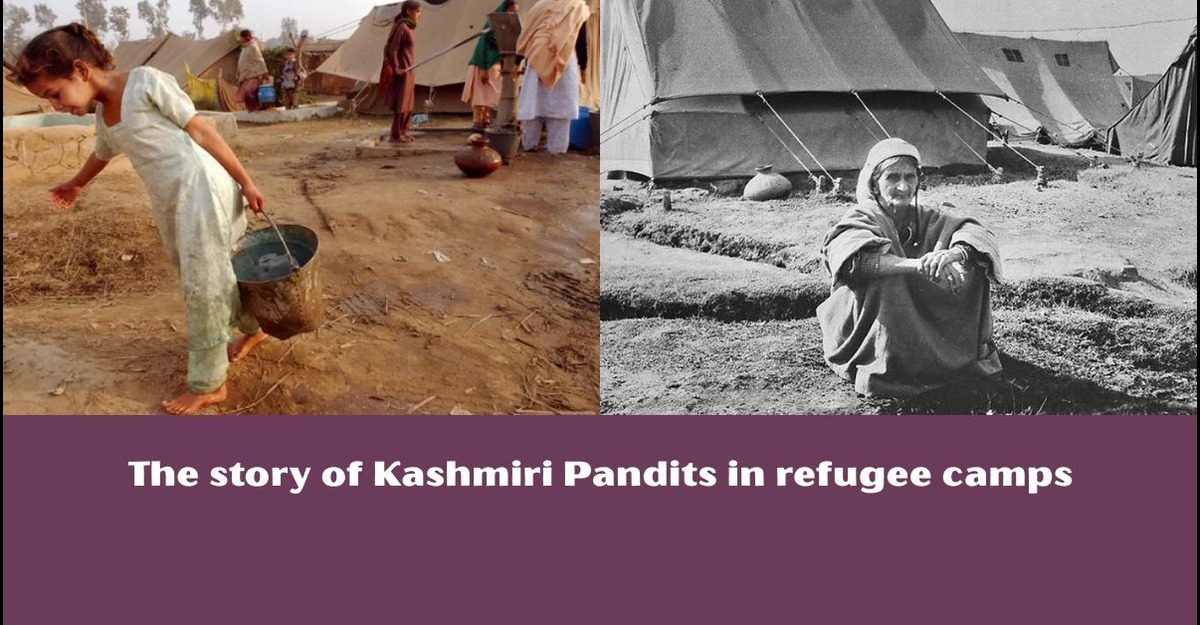

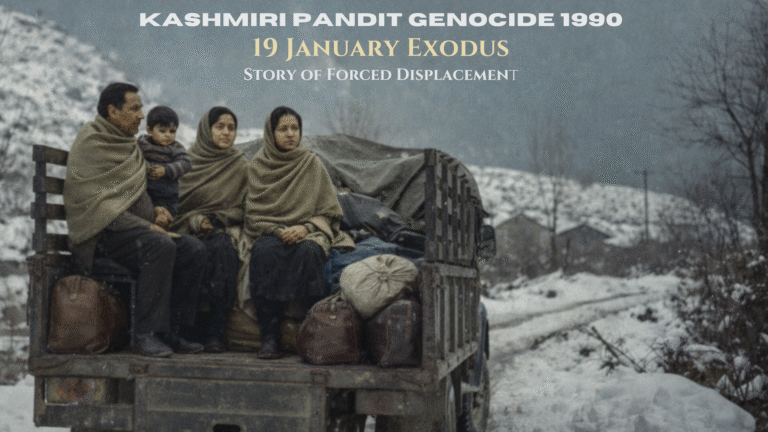

The story of Kashmiri Pandits in refugee camps is one we must collectively remember and share. Following the 1990 forced departure, many people were driven from their homes in the Kashmir Valley and had to live in temporary shelters in Jammu and other areas of India.

“A genocide begins with the killing of one man, not for what he has done but because of who he is.”– Kofi Annan

For the Kashmiri Pandit community, that man was Tika Lal Taploo, a senior community leader who was brutally murdered in September 1989. His assassination was not the killing of an individual. It was the first in a series of events that would force an entire community to abandon their ancestral homeland and go to the refugee camps of Udhampur, Jammu, and Delhi.

The story of Kashmiri Pandits in refugee camps is not only about displacement but also about the psychological trauma we endured. Families who had lived in areas with apple orchards, temples, and culture were now forced into small, shared rooms.

The Panic and Confusion: Nowhere to Go

When Kashmiri Pandits left their valley homes, we were overwhelmed by panic and confusion. Most families had no clear destination in mind. We knew we had to go immediately to save our lives. The journey was chaotic and frightening. Families separated in the rush, belongings were left behind, and children cried as they were pulled away from familiar surroundings.

The first stops for many families were Udhampur and Jammu. These were the nearest safe destinations outside the valley, but arriving there brought new challenges. The displaced families were unsure of what to do next, where to go, or how to rebuild their lives. We found ourselves in unfamiliar territory, without jobs, without homes, and with no clear plan for survival.

Families spent their first nights at the Udhampur and Jammu bus stations. Parents clutched their children, offering comfort while battling their own fears and anxieties. The community, once thriving with homeowners and professionals, was now homeless and dependent on charity.

Geeta Bhawan and Community Halls: The First Stop

Upon arriving in Jammu, we were without lodging. Community halls, schools, and Geeta Bhawan provided us with temporary housing. Families that used to live on their own were forced to live together in small spaces, sometimes with four families sharing one room. Saris served as makeshift dividers, offering a semblance of privacy that was quickly lost.

Mothers cooked in cramped corners while children struggled to sleep nearby. The air was thick with noise, smoke, and the constant cries of children. Though these halls were never intended for residential use, they became our first step towards survival.

From Temples to Tents

Once it was apparent that the displacement wouldn’t be short-lived, officials understood that community halls and temples weren’t suitable for long-term housing. Consequently, the government started setting up tent cities in different areas around Jammu and Udhampur. A major camp was established at Battalbaliyan in Udhampur.

In Jammu, multiple camps were established in places like Muthi, Purkhoo, Mishriwala, Nagrota, and Jhiri. Thousands of displaced Kashmiri Pandit families found refuge in these locations. While the tents offered more organised living spaces compared to community halls, they also presented their own difficulties.

Families usually received a tent about 12 feet by 12 feet. Larger families, those with eight or more members, found this space incredibly cramped. Several generations lived in this small canvas shelter, sharing the space without dividers for sleeping, cooking, or storage.

A lot of camps had one toilet for almost a hundred families to use. The dirty lavatory systems overflowed and lacked maintenance. Women queued late at night for a small measure of privacy. Jammu’s harsh summer of 45°C killed many elderly Pandits. Monsoons turned tents into waterlogged swamps, while winters froze the ground beneath us. The story of Kashmiri Pandits in the refugee camps during this phase was defined by humiliation and disease.

One-Room Tenements: No Relief in Concrete Walls

By 1996, authorities constructed concrete one-room tenements measuring 9 by 12 feet (108 square feet). While providing better weather protection than tents, families of varying sizes were all allocated the same small space. All activities continued in one cramped room with poor ventilation.

Many families created makeshift kitchens along walls. Children had no private study space, continuing to study outside under streetlights. These concrete structures felt like “concrete cages” rather than dignified housing.

Heat Crisis: A Deadly Aspect of the Plight

The impact of climate change was significant. Those used to the cold mountains of Kashmir were suddenly exposed to the extreme heat of Jammu, which hit 45°C (113°F). The Kashmiri Pandits’ suffering in the refugee camps was worsened by the tents turning into ovens.

Heatstroke became common, claiming lives among elderly residents who couldn’t adapt. Many families lost grandparents during these difficult early years. Dehydration was constant, but access to clean, cool water was limited. Some families reported fearing the scorching heat more than the militancy they’d left behind.

The monsoon season caused problems. Tents got wet, and beds became soggy. There was mud, and mould grew because of the dampness.

Educational Struggles

Impact on Learning

Children’s education suffered severely. Cramped tents meant there were no quiet study spaces; studying, sleeping, and cooking all took place in the same area. Children often studied outside under streetlights.

Evening Colleges

Educational authorities established evening colleges in Jammu for displaced students. While local students attended day shifts, Kashmiri Pandit students studied from late afternoon until night. The teaching staff was limited, with fewer teachers, larger classes, and less individual attention than in regular institutions.

Unfortunately, we were connected to Kashmir, not Jammu University, which meant students took longer to finish their education because of the strikes and disruptions in Kashmir. Students faced a lathi charge for fighting to hold exams, typically. We were deprived, and careers were finished.

What happened to the Kashmiri Pandit students? Why were they Lathicharged? Read my book?

Jagti Settlement in 2011: A New Chapter of Displacement

In 2011, many Kashmiri Pandit families were relocated to the Jagti migrant colony, about 25 kilometers from Jammu city, marking their third displacement since the 1990 exodus. Initially living in multiple makeshift camps like Muthi, Purkhoo, and Nagrota.

The move to Jagti was meant to offer better housing and improved living standards through a planned township of over 4,200 two-room flats.

This relocation was a governmental effort to provide permanent housing and to stop decades of tent living and insufficient shelters.

Despite the hopes pinned on Jagti as a solution, residents faced challenges, including poorly constructed flats with structural cracks, water seepage, and inadequate infrastructure. Economic and social instability persisted, as many individuals lost their previous businesses or livelihoods during the transition.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Kashmiri Pandits in Refugee Camps

Q: What caused the displacement of Kashmiri Pandits in 1990?

A: The displacement began following the assassination of senior community leader Tika Lal Taploo in 1989, which marked the start of targeted violence, forcing the entire community to flee their ancestral homeland.

Q: Where were Kashmiri Pandits initially housed after fleeing the valley?

A: Many first found refuge in bus stations of Udhampur and Jammu, then moved to cramped community halls, schools, and temples such as Geeta Bhawan, before being relocated to tent camps in various locations around Jammu and Udhampur.

Q: What were the living conditions like in the tent camps?

A: Families lived in cramped 12-by-12-foot tents, often with multiple generations sharing the space. Camps had inadequate sanitation, with often one toilet serving hundreds of families, leading to disease and humiliation.

Q: How did the climate affect Kashmiri Pandits in the refugee camps?

A: Used to cold mountain weather, many suffered from extreme heat in Jammu’s 45°C summers, leading to heat strokes and deaths, especially among elderly residents. Monsoons caused waterlogging and tent damage, while winters were harsh.

Q: How were education and learning affected for displaced Kashmiri Pandit children?

A: Children lacked proper study spaces due to cramped housing and often studied outside under streetlights. Evening colleges were set up with limited staff and resources, causing delays in education and additional years to complete studies.

Q: What accommodations were made for Kashmiri Pandits in 2011?

A: Many families were relocated to the Jagti migrant colony near Jammu in a planned township of over 4,200 two-room flats, aiming to provide better housing after decades in tents and temporary shelters.

Q: Have promises been made about resettlement or relief in elections?

A: Election manifestos in 2014 and 2019 included promises related to resettling Kashmiri Pandits, but no substantial resettlement or relief measures have been effectively implemented since then.

Q: Why is there frustration about relief assistance?

A: Relief and rehabilitation support have often been limited, with no significant extensions since 2018. The community feels relief efforts are largely symbolic and tend to surface only during election periods without meaningful action.

Q: Who were the Indian leaders during the 1990 Kashmiri Pandit exodus?

A: Vishwanath Pratap Singh was the Prime Minister of India in 1990, and Mufti Mohammad Sayeed was the Home Minister responsible for Jammu and Kashmir during the exodus.