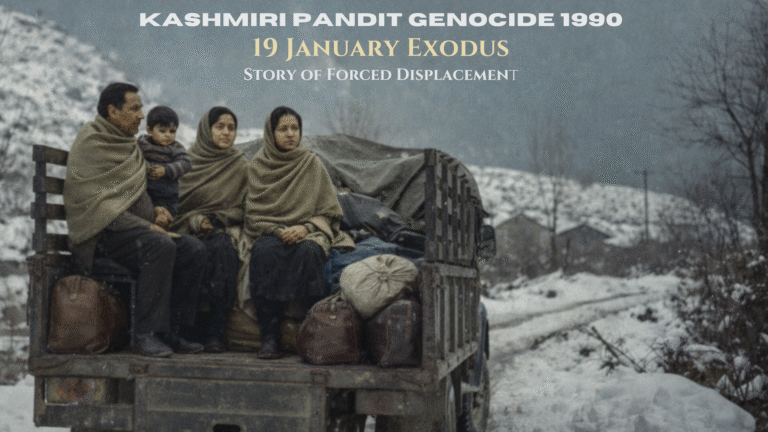

The Kashmiri Pandits left Kashmir because staying meant death. Between 1989 and 1991, approximately 300,000 to 350,000 Kashmiri Pandits fled the Valley. This was not migration. It was ethnic cleansing driven by targeted violence, religious extremism, and state failure.

The Groundwork Was Laid Decades Earlier

The exodus of 1990 did not emerge from nowhere. The foundations were constructed through years of political decisions and ideological shifts.

Post-Independence Marginalisation

After 1947, Kashmir’s political landscape transformed. By the 1970s, Kashmiri Pandits experienced systematic exclusions. Government jobs increasingly favoured the Muslim majority. Educational opportunities for Hindu students diminished. Social spaces that once welcomed all communities became religiously segregated.

These exclusions represented a systematic erosion of minority rights that would later enable complete removal.

The Birth of Armed Militancy

Maqbool Bhat initiated a separatist organisation in Kashmir after founding precursor groups in 1965. His ideology rejected Indian sovereignty and envisioned Kashmir as an Islamic state where religious minorities had no future.

The Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front was formally established on 29 May 1977 in Birmingham, England. Maqbool Bhat and Amanullah Khan co-founded the JKLF as an armed organisation dedicated to Kashmiri independence through violence.

Bhat’s execution in 1984 transformed him into a martyr. His followers embraced violence as legitimate politics. They drew inspiration from global jihad movements gaining momentum in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

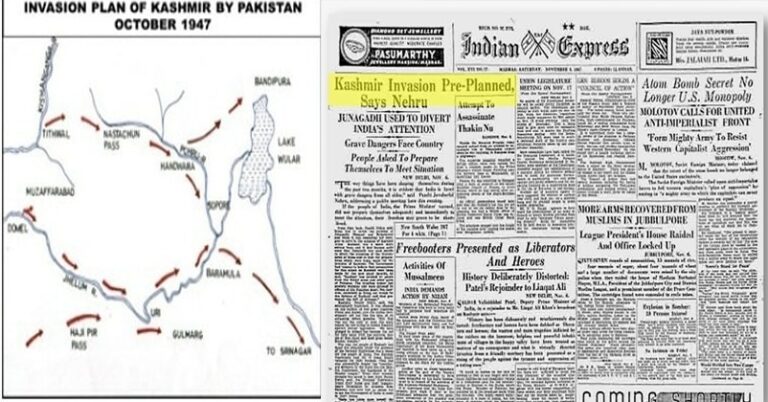

Pakistan’s Strategic Intervention

The Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989 proved catastrophic for Kashmir. Thousands of battle-hardened militants needed a new cause. Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence redirected them towards Kashmir under Operation Tupaq.

General Zia-ul-Haq’s doctrine of “a thousand cuts” made Kashmir the primary battleground. Pakistan established training camps, indoctrinated young Kashmiris, and supplied weapons and funds. The strategy aimed to destabilise Indian control and create conditions for ethnic cleansing to alter demographics permanently.

The 1986 Anantnag Riots

In early 1986, Anantnag district witnessed sudden communal violence. Temples were attacked. Hindu homes were vandalised. Thousands of Kashmiri Pandits were targeted in what many believe was engineered violence.

This was the first clear signal that Kashmiri Pandits were being marked for elimination. The riots demonstrated that communal violence against the minority could occur with minimal consequences. It was a rehearsal for 1990.

The 1987 Election Rigging

The 1987 Jammu and Kashmir Assembly elections became a watershed moment. The National Conference and Congress coalition blatantly rigged the results to prevent the Muslim United Front from winning.

Young Kashmiris who believed in democratic change felt betrayed. Many turned to militancy, convinced that peaceful politics was futile. Pakistan’s ISI actively recruited these disillusioned youth.

Leaders like Yasin Malik abandoned political activism for armed struggle. The JKLF gained recruits and legitimacy among educated, urban Kashmiri Muslims who previously rejected violence.

This radicalisation created fertile ground for ethnic cleansing.

1989: When Violence Became Lethal

The Rubaiya Sayeed Kidnapping

On 8 December 1989, terrorists kidnapped Rubaiya Sayeed, the daughter of Home Minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed. The JKLF demanded the release of five imprisoned militants.

After five days, the Indian government capitulated. It released all five terrorists in exchange for her return.

This decision had catastrophic consequences. It demonstrated that terrorism worked and violence paid. Militant groups gained unprecedented confidence. Recruitment surged overnight.

Kashmiri Pandits watched this surrender with growing dread. They knew they would be the following targets.

Systematic Assassinations Begin

Terrorists began systematically murdering prominent Kashmiri Pandits months before the mass exodus. These were not random killings. Each victim was carefully selected to maximise fear and deliver specific messages.

Tika Lal Taploo, a respected lawyer and BJP leader, was shot dead outside his Srinagar home on 14 September 1989. His assassination marked the beginning of targeted violence against Hindu leaders. Terrorists wanted to eliminate any potential resistance.

Justice Neelkanth Ganjoo was murdered on 4 November 1989. Terrorists blamed him for sentencing Maqbool Bhat to death. His killing sent a chilling message: no Pandit was safe, regardless of status or profession.

Between September 1989 and January 1990, dozens of Kashmiri Pandits were assassinated. Each killing followed a pattern: sudden, brutal, public, and unpunished. The state offered no protection. Police investigations led nowhere. Terrorists operated with complete impunity.

The Strategy Behind Murders

These assassinations served calculated purposes.

They eliminated potential resistance leaders who might organise community defence. They terrorised ordinary Pandits into submission and flight. They demonstrated state impotence and militant strength. They broke the social fabric that had held Kashmiri society together for centuries.

Muslims who might have protected their Pandit neighbours feared becoming targets themselves. The message was clear: helping Pandits meant death.

The Political Power Vacuum

In January 1990, political manoeuvring created chaos precisely when strong leadership was needed.

Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, as Home Minister, pushed for Jagmohan’s reappointment as Governor. This strategic move targeted Farooq Abdullah, who had a history with Jagmohan dating to 1984.

Farooq resigned on 18 January 1990 upon learning of Jagmohan’s reappointment. Jagmohan was sworn in on 19 January but couldn’t reach Srinagar due to bad weather.

That same night, mosques broadcast expulsion orders. Kashmiri Pandits faced an existential threat, with no functioning state government and inadequate protection.

19 January 1990: The Night Kashmir Changed Forever

The Mosque Announcements

As darkness fell on 19 January 1990, loudspeakers from mosques across the Valley broadcast messages. The intent was unmistakable: Kashmiri Pandits must leave Kashmir immediately or face consequences.

Slogans echoed through the freezing winter night:

“Raliv, Galiv ya Chaliv” – Convert to Islam, leave Kashmir, or die.

“Asi gachiv panun Pakistan, Batav ros-ta batanev san” – We will create our Pakistan, with Pandit women and without Pandit men.

“Yahan kya chalega, Nizam-e-Mustafa” – Only Islamic law will prevail here.

“Kashmir mein agar rehna hai, Allah-O-Akbar kehna hai” – To live in Kashmir, you must say Allah-O-Akbar.

“Kafiro, Kashmir chhodo” – Infidels, leave Kashmir.

The Printed Threats

The terror was systematic and multi-pronged.

Local Urdu newspapers published explicit warnings. Alsafa and Aftab carried notices ordering Pandits to leave within 48 hours.

Wall posters appeared across homes, names of Pandit families marked for death. Hit lists circulated identifying specific targets by name, address, and profession. Hindu-owned shops were marked with distinctive symbols.

This was systematic psychological warfare designed to create maximum terror and force mass departure.

Coexistence ended in a single night.

Why Leaving Became the Only Option

By January 1990, Kashmiri Pandits faced an impossible situation.

Targeted killings had eliminated community leaders and created pervasive fear. Anyone could be next. Murders occurred in broad daylight with no arrests, no investigations, no justice.

Public death threats broadcast from mosques carried religious sanction. These weren’t empty warnings; they were accompanied by actual murders proving militants meant what they said.

Newspaper warnings with 48-hour deadlines created immediate panic. Families had to decide: stay and potentially die, or flee and lose everything.

Complete social isolation meant no protection from neighbours or friends. The community safety net had evaporated. People who once offered help now looked away or actively participated in threats.

State abandonment meant no police protection, no army intervention, no government rescue. Authorities either couldn’t or wouldn’t protect them. When Pandits reported threats, police did nothing. When murders occurred, investigations went nowhere.

Explicit sexual threats against women made remaining unthinkable for families. The threat “Batav ros-ta batanev san” (with your women, without your men) was not metaphorical. It was a promise of mass rape and forced conversion.

Staying meant waiting to be killed, converted, or watching female family members being violated. Leaving meant losing homes, property, temples, businesses, and a 5,000-year heritage. But at least it meant survival.

Terror Organisation Coordination

Multiple militant organisations coordinated the ethnic cleansing:

JKLF focused on assassinating prominent Pandit leaders and intellectuals to eliminate potential resistance.

Hizbul Mujahideen handled mass intimidation through public threats, graffiti, and mosque announcements.

This was organised terror with clear objectives: to eliminate Kashmir’s Hindu minority and create an Islamic state.

Frequently Asked Questions About Kashmiri Pandit Exodus

Why did the Kashmiri Pandits leave Kashmir?

Kashmiri Pandits left Kashmir because staying meant death. Between 1989 and 1991, terrorists from JKLF and Hizbul Mujahideen systematically targeted them through assassinations, threats, and violence. On 19 January 1990, mosques across the Valley broadcast expulsion orders threatening Hindus to convert, leave, or die. Approximately 350,000-400,000 Pandits fled their ancestral homeland within two years due to this ethnic cleansing campaign.

What happened on 19 January 1990 in Kashmir?

On the night of 19 January 1990, loudspeakers from mosques across Kashmir broadcast threatening slogans ordering Kashmiri Pandits to leave immediately. The most infamous slogan was “Raliv, Galiv ya Chaliv” (Convert to Islam, leave Kashmir, or die). Local newspapers Alsafa and Aftab published notices giving Pandits 48 hours to depart. This coordinated intimidation campaign marked the peak of ethnic cleansing that had begun months earlier with targeted assassinations.

Was the Kashmiri Pandit exodus voluntary or forced?

The Kashmiri Pandit exodus was absolutely forced, not voluntary. It meets the international definition of ethnic cleansing: systematic removal of an ethnic or religious group through force and intimidation. Pandits fled because terrorists were actively killing prominent community members, issuing death threats, broadcasting expulsion orders from mosques, and committing brutal atrocities, including rape and torture. They left barefoot in overcrowded trucks with no belongings, abandoning homes, property, and temples. This was survival, not choice.

Who was responsible for the Kashmiri Pandit exodus?

Terrorist organisations, including the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), Hizbul Mujahideen, Lashkar-e-Taiba, and Jaish-e-Mohammed, were directly responsible for the ethnic cleansing. These groups, supported and trained by Pakistan’s ISI, systematically assassinated Pandit leaders, issued death threats, broadcast expulsion orders, and committed atrocities to force the Hindu minority out. The Indian government failed catastrophically to protect its citizens despite intelligence warnings months before the violence escalated.

How many Kashmiri Pandits were killed during the exodus?

Whilst exact numbers remain disputed, hundreds of Kashmiri Pandits were killed between 1989 and 1990. Prominent victims included Tika Lal Taploo (14 September 1989), Justice Neelkanth Ganjoo (4 November 1989), and many others. Documented atrocities include brutal torture murders like Sarwanand Kaul Premi (drilled with electric drills), Girija Tickoo (gang-raped and sawed in half on 25 June 1990), and B.K. Ganjoo (burned alive in a rice drum). The Nadimarg Massacre in 2003 killed 24 Pandits, proving violence continued years later.

Was Jagmohan responsible for the Kashmiri Pandit exodus?

No, Jagmohan was not responsible for the exodus. This is a politically convenient myth. The facts prove otherwise: targeted killings began months before Jagmohan took office on 19 January 1990 (Taploo killed in September 1989, Ganjoo in November 1989). Jagmohan wasn’t even in Srinagar on 19 January when mosque announcements intensified—he was stuck in Jammu due to bad weather. He publicly appealed to Pandits not to leave and pledged protection. Editor Ghulam Mohammed Sofi called, blaming Jagmohan, “systematic propaganda” and a “total lie.”

What were the slogans used against Kashmiri Pandits?

The slogans broadcast from mosques on 19 January 1990 included: “Raliv, Galiv ya Chaliv” (Convert, leave, or die), “Asi gachiv panun Pakistan, Batav ros-ta batanev san” (We will create our Pakistan with your women, without your men), “Yahan kya chalega, Nizam-e-Mustafa” (Only Islamic law will prevail), “Kashmir mein agar rehna hai, Allah-O-Akbar kehna hai” (To live in Kashmir, say Allah-O-Akbar), and “Kafiro, Kashmir chhodo” (Infidels, leave Kashmir). These slogans made the religious motivation for ethnic cleansing explicit.

How many Kashmiri Pandits left Kashmir?

Approximately 300,000 to 350,000 Kashmiri Pandits fled Kashmir between 1989 and 1991. By March 1990, over 100,000 had fled. By year’s end, the number exceeded 300,000. Within two years, Kashmir’s Hindu population was virtually eliminated from the Valley. A community that had lived in Kashmir for over 5,000 years was ethnically cleansed in less than 24 months.

What was the rigging in the 1987 Kashmir election?

The National Conference and Congress coalition blatantly rigged the 1987 Jammu and Kashmir Assembly elections to prevent the Muslim United Front from winning. This betrayal devastated young Kashmiris who believed in democratic change. Many turned to militancy, convinced that peaceful politics was futile. Pakistan’s ISI actively recruited these disillusioned youth. Leaders like Yasin Malik abandoned political activism for armed struggle. This election rigging directly fuelled the radicalisation that led to ethnic cleansing three years later.

What was the Rubaiya Sayeed kidnapping?

On 8 December 1989, JKLF terrorists kidnapped Rubaiya Sayeed, daughter of Home Minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed. They demanded the release of five imprisoned militants. After five days, the Indian government capitulated and released all five terrorists. This decision had catastrophic consequences—it demonstrated that terrorism worked and violence paid dividends. Militant groups gained unprecedented confidence, and recruitment surged. Kashmiri Pandits watched this surrender and knew they would become the next targets.

Were Kashmiri Pandits given any warning before the exodus?

Yes, Kashmiri Pandits received multiple warnings. Local Urdu newspapers Alsafa and Aftab published explicit notices ordering Pandits to leave within 48 hours. Wall posters appeared listing the names of Pandit families marked for death. Hit lists circulated identifying specific targets by name, address, and profession. Hindu-owned shops were marked with distinctive symbols. However, these “warnings” were not protective—they were part of systematic psychological warfare designed to terrorise the community into fleeing.

What happened to the Kashmiri Pandit properties after they left?

Immediately after the Pandits fled, their properties were illegally occupied and looted. Homes were seized by neighbours or sold to new occupants. Agricultural land, cultivated for centuries, was taken over. Business properties were occupied. This property theft served two purposes: financially rewarding those who participated in ethnic cleansing, and ensuring Pandits could never return by eliminating their economic base. Ancient Hindu temples were desecrated, vandalised, or destroyed. No legal mechanism exists to recover these properties.

What role did Pakistan play in the Kashmiri Pandit exodus?

Pakistan played a central role through its Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). After the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989, Pakistan redirected thousands of battle-hardened militants towards Kashmir under Operation Tupaq. This was part of General Zia-ul-Haq’s “death by a thousand cuts” doctrine. Pakistan established training camps, provided weapons and funds, and indoctrinated young Kashmiris. Pakistan-based groups like Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed coordinated with local militants to execute ethnic cleansing aimed at creating demographic change favourable to Pakistan’s territorial claims.

Why didn’t the Indian government protect Kashmiri Pandits?

The Indian government catastrophically failed despite having intelligence warnings months before violence escalated. Security forces were never adequately deployed to Pandit neighbourhoods. Local police were unable or unwilling to act when families reported threats; nothing happened. When murders occurred, investigations went nowhere. Political manoeuvring in January 1990 created a power vacuum precisely when protection was needed. The army deployment came too late and focused on border areas rather than protecting civilians in towns. This was a complete failure of the state’s fundamental duty to protect its citizens.

What were the 1986 Anantnag riots?

In early 1986, Anantnag district experienced sudden communal violence where temples were attacked, and Hindu homes were vandalised. Thousands of Kashmiri Pandits were targeted in what many believe was engineered violence. This was the first clear warning that Pandits were being marked for elimination. The riots demonstrated that communal violence against the minority could occur with minimal consequences. It was effectively a rehearsal for the systematic ethnic cleansing that would occur four years later in 1990.

How did Kashmiri Pandits actually leave Kashmir?

Most Kashmiri Pandits escaped in overcrowded local trucks with five or six families packed into single vehicles. They travelled barefoot through freezing January weather. There were no organised government buses or systematic evacuation—this is a myth. Families fled with only what could fit in a small bag, abandoning homes, valuables, and centuries of belongings. Many left at night, fearing daytime departure would mark them as targets. They left doors unlocked and meals half-eaten. It was a desperate, chaotic flight for survival, not an orderly migration.

What does “Raliv, Galiv ya Chaliv” mean?

“Raliv, Galiv ya Chaliv” is a Kashmiri phrase meaning “Convert to Islam, leave Kashmir, or die.” This slogan was broadcast from mosque loudspeakers across the Valley on the night of 19 January 1990. It explicitly gave Kashmiri Pandits three options: religious conversion (Raliv), exodus (Chaliv), or death (Galiv). This slogan encapsulates the religiously motivated ethnic cleansing—it was an ultimatum that made clear Hindus had no future in Kashmir unless they abandoned their faith or their homeland.

Were any Muslims killed during the Kashmir conflict?

Yes, Muslims were also killed during the Kashmir conflict, primarily in encounters between security forces and militants, and through terrorist violence. However, this is a separate issue from the ethnic cleansing of Kashmiri Pandits. The systematic targeting of Pandits specifically because of their religion, with explicit goals of removing them from Kashmir, constitutes ethnic cleansing. The violence against the Muslim population occurred in the context of counter-insurgency operations, not religious persecution aimed at the elimination of an entire community.

Why is the Kashmiri Pandit exodus not widely known?

The Kashmiri Pandit exodus remains relatively unknown due to multiple factors: Indian national media provided insufficient coverage as it unfolded; international media largely ignored the story; the narrative of Kashmir has focused predominantly on other aspects of the conflict; politically convenient myths (like blaming Jagmohan) obscure the truth of militant-led ethnic cleansing; and some intellectuals and separatists actively deny or minimise what happened. The result is that one of India’s most significant cases of ethnic cleansing remains inadequately recognised globally, compounding the trauma of survivors.