BJP’s Kashmir policy of 1990 operated through a paradox: proximity to power without the will to exercise it. While the party provided external support to V.P. Singh’s fragile coalition government, this positioning never translated into protective action for Kashmiri Pandits facing systematic violence and displacement.

This analysis explores how electoral calculations shaped Kashmir policy decisions in 1990, why minority protection became secondary to broader political mobilisation, and what the gap between rhetoric and action meant for the minority community that lost their homeland. Understanding this period requires examining not just what happened, but also the choices that defined the response when prevention was still possible.

Why Did the Kashmiri Pandit Exodus Happen Despite BJP Support at the Centre?

The question assumes support equals responsibility. It assumes proximity to power translates into action.

History proves otherwise.

External support is not governance. The BJP propped up V.P. Singh’s administration without holding a single cabinet position, without controlling security forces, without administrative authority over Jammu and Kashmir.

But they possessed something potent: the ability to end the government at will.

This raises the sharper question: when did they choose to exercise that power, and for what cause?

How BJP’s Kashmir Policy of 1990 Revealed Selective Priorities

October 1990: The Rath Yatra Response

L.K. Advani’s Rath Yatra rolled through northern India in September and October 1990, drawing massive crowds and building momentum for the Ayodhya movement. When Lalu Prasad Yadav ordered the arrest of Advani in Bihar on October 23rd, the BJP’s response was immediate and unambiguous.

They withdrew support. The government fell.

The party demonstrated it knew exactly how to wield its leverage when its own priorities faced obstruction.

Meanwhile in Kashmir: Warning Signs Ignored

Meanwhile, Kashmiri Pandits were receiving death threats, seeing inflammatory graffiti on their homes, and beginning to flee in growing numbers. The violence would peak in January 1991, but the warning signs flashed bright throughout 1990.

No ultimatums were issued. No support was withdrawn. No government fell.

The contrast in response reveals the brutal arithmetic of political calculation.

Electoral Mathematics Behind Kashmir Policy Decisions 1990

The Numbers That Shaped Priorities

Electoral politics runs on mathematics, not morality.

Kashmiri Pandits numbered roughly 140,000 in the Valley. Geographically concentrated in a single state where the BJP had virtually zero presence. Politically insignificant in terms of seat calculations or vote consolidation.

Ayodhya vs Kashmir: A Strategic Choice

Compare this to the Ayodhya mobilisation.

The Ram Janmabhoomi campaign offered access to millions of voters across Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and beyond. It provided the ideological glue that bound diverse Hindu communities. It created the visibility and momentum that would carry the BJP to power.

One cause offered transformation. The other offered only moral obligation.

Political parties make choices. This was theirs.

Kashmir Crisis Before 1990: The Buildup to Exodus

1986: When Communal Politics Entered Mainstream

Pretending the exodus appeared suddenly in 1990 requires willful ignorance of Kashmir’s trajectory through the 1980s.

1986 marked a turning point. Under Ghulam Mohammad Shah’s government, communal rhetoric entered mainstream political discourse. Religious polarisation became a tool rather than a taboo. The social fabric began fraying in ways that would prove irreversible.

1987 Election Rigging: The Fatal Turning Point

1987 delivered the fatal blow. The rigged Assembly elections destroyed faith in democratic processes among Kashmiri Muslim youth. When the system demonstrated that it would not allow political change through peaceful means, violence became attractive.

Pakistan’s Role: Weaponising Existing Grievances

Pakistan’s ISI didn’t create this alienation. Indian political mismanagement did. Pakistan simply weaponised existing grievances, providing training, funding, and an ideological framework that turned religious identity into a battle line.

Kashmiri Pandits became targets because they were visible, vulnerable, and strategically useful for creating terror.

December 1989: The Rubaiya Sayeed Kidnapping and State Capitulation

When the Government Blinked

Mufti Mohammad Sayeed took office as Union Home Minister in December 1989. His daughter Rubaiya’s kidnapping by militants weeks later created a crisis that would define what followed.

The government negotiated. Five imprisoned terrorists walked free in exchange for her release.

Consequences of Capitulation

That capitulation sent shockwaves through the entire security architecture.

Militants learned that violence works. Security forces learned that political leadership lacked resolve. Kashmiri Pandits learned that the state would not protect them when confrontation was required.

Every subsequent decision operated in the shadow of that surrender.

BJP’s Political Leverage in 1990: Used and Unused Options

What Real Leverage Looks Like

The claim that the BJP lacked power rings hollow, given what we know about how they actually used their position.

Real leverage sounds like this:

“Central forces deploy to protect minority areas immediately, or this government ends tomorrow.”

“Every police officer complicit in violence gets arrested and prosecuted, or we walk.”

“Security protocols for vulnerable communities become non-negotiable, or you find new allies.”

What the BJP Actually Offered

Instead, the party offered:

Statements of concern. Parliamentary speeches. Press conference condemnations.

The difference between these approaches defines the difference between politics as theatre and politics as consequence.

From the 1990 Kashmir Policy to the Current Political Rhetoric

The Pattern of Symbolic Politics

Three and a half decades later, Kashmiri Pandits remain a rhetorical device.

Their suffering gets invoked in speeches about minority persecution, secular hypocrisy, and historical wrongs. The exodus serves as Exhibit A in arguments about appeasement and civilizational conflict.

The Gap Between Rhetoric and Rehabilitation

Meanwhile:

Rehabilitation efforts remain fragmented and inadequate. Compensation programs fail to address the scale of loss. Return to the Valley stays perpetually “under consideration.” Justice remains abstract rather than actionable.

This community proved more valuable as a symbol than as a constituency requiring actual policy commitment.

Cross-Party Failure with Unequal Accountability

The pattern holds across party lines. Everyone failed the Pandits at different points and in different ways. But when a party builds significant political capital on invoking their tragedy, the gap between rhetoric and remedy becomes particularly stark.

Shared Responsibility: Multi-Party Failures in Kashmir 1990

Congress and Pre-1989 Deterioration

Multiple actors bear responsibility for what happened in 1990 and 1991.

Congress governments before 1989 allowed communal polarisation to take root. The rigged 1987 election created the conditions for militancy. Jammu and Kashmir’s local administration proved either unwilling or unable to maintain order.

Pakistan’s Direct Role

Pakistan’s ISI actively fueled violence. The central government, regardless of composition, failed to respond with adequate force.

BJP’s Strategic Choice

And the BJP chose electoral consolidation over minority protection.

They possessed leverage. They demonstrated they knew how to use it. They deployed it for Ayodhya. They withheld it for Kashmir.

That constitutes a choice, not a constraint.

Lessons from the BJP Kashmir Policy 1990 for Minority Protection Today

Why Historical Analysis Still Matters

Because the same calculations still govern political behaviour.

Communities remain valuable or expendable based on their electoral utility. Symbolic invocation substitutes for material action. Leverage gets preserved for core political projects while peripheral communities face their crises alone.

The Core Truth About Prevention

The exodus didn’t happen because protection was impossible. It happened because protection wasn’t politically profitable.

Until we confront that reality directly, we’ll continue witnessing preventable tragedies while those with the power to prevent them choose not to act.

What the Record Shows

The historical record on Kashmir isn’t ambiguous. The timelines are clear. The choices are documented. The priorities are revealed through both action and inaction.

What remains is whether we’re willing to acknowledge what those choices actually meant for the people who paid the price.

This is not an argument for partisan advantage. It’s an argument for understanding how political power actually operates when electoral incentives conflict with moral imperatives. The Kashmiri Pandit exodus offers a case study in that conflict, and in what happens when the incentives win.

For a detailed analysis of policy contradictions and their consequences,

Here is the deeper context and historical analysis.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Kashmiri Pandit Exodus

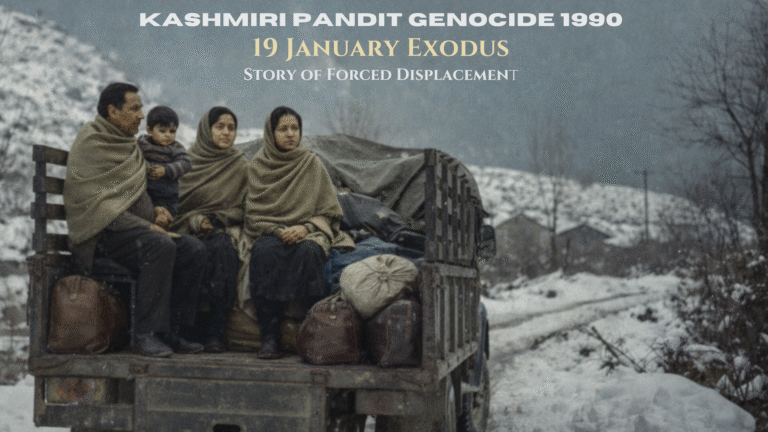

When did the Kashmiri Pandit exodus happen?

The Kashmiri Pandit exodus occurred primarily between January and March 1990, though violence against the community had been escalating since the mid-1980s. The peak of forced migration happened in January 1991, when large-scale targeted killings forced entire neighbourhoods to flee overnight. This ethnic cleansing in Kashmir displaced approximately 140,000 Kashmiri Hindus from the Kashmir Valley, marking one of the most significant cases of religious minority persecution in modern Indian history.

Why did Kashmiri Pandits leave Kashmir in 1990?

Kashmiri Pandits fled Kashmir due to systematic targeted violence, death threats, and religious persecution by militants. Armed terrorists posted threatening notices on Hindu homes, selective killings of prominent community members occurred, and slogans like “Raliv, Tsaliv ya Galiv” (convert, leave, or die) created an atmosphere of terror. The failure of the state security apparatus, combined with police complicity and lack of central government intervention, made survival impossible. This was not voluntary migration but forced displacement driven by Islamic extremism supported by Pakistani ISI operations in Kashmir.

What was the BJP’s role during the 1990 Kashmiri Pandit exodus?

The BJP supported V.P. Singh’s government from outside during the exodus period but never used this leverage to protect Kashmiri Pandits. While the party had the power to withdraw support and collapse the government, they reserved this option for the Ayodhya movement, not Kashmir. When L.K. Advani was arrested during his Rath Yatra in October 1990, the BJP immediately withdrew support, demonstrating they could act decisively when their core political priorities were threatened. This selective use of political leverage reveals the electoral calculations that governed their Kashmir policy.

How many Kashmiri Pandits were killed in the exodus?

Estimates of Kashmiri Pandit deaths vary, with documented killings ranging from several hundred to over a thousand during the 1990-1991 violence. Many were targeted assassinations of prominent community members, including judges, government officials, teachers, and political activists. The actual number remains disputed due to inadequate documentation, ongoing violence during the exodus, and deaths from displacement-related hardships. Beyond direct killings, the psychological trauma, loss of property, and cultural genocide affected the entire 140,000-strong community.

What was the rigging in the 1987 Kashmir election?

The 1987 Jammu and Kashmir Assembly elections were widely regarded as massively rigged in favour of the Farooq Abdullah-Rajiv Gandhi alliance over the Muslim United Front (MUF). This electoral fraud destroyed faith in democratic processes among Kashmiri Muslim youth, many of whom later joined militant groups. The rigging is considered a major turning point that fuelled the Kashmir insurgency, as it demonstrated that peaceful political change was impossible, making armed rebellion attractive. This democratic failure created the conditions that Pakistan’s ISI later exploited.

Who was responsible for the Kashmiri Pandit genocide?

Responsibility for the Kashmiri Pandit exodus is shared across multiple actors. Pakistan’s ISI actively funded and trained militants who carried out the violence. Kashmiri separatist groups like JKLF executed the targeted killings. The V.P. Singh government failed to deploy adequate security forces. Mufti Mohammad Sayeed’s decision to release militants in exchange for his daughter created a perception of state weakness. The Jammu and Kashmir police included complicit elements who enabled violence. The BJP, despite supporting the central government, chose not to use their political leverage to force protective action. This was a systemic failure across institutions.

What happened after Rubaiya Sayeed’s kidnapping in 1989?

Rubaiya Sayeed, daughter of Union Home Minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, was kidnapped by militants on December 8, 1989, just five days after her father took office. The government negotiated and released five imprisoned terrorists in exchange for her freedom on December 13, 1989. This capitulation to militant demands had devastating consequences: it emboldened terrorist groups, demoralised security forces, and signalled that the state lacked resolve. The Rubaiya Sayeed case is considered a pivotal moment that accelerated the collapse of state authority in Kashmir and contributed directly to the exodus that followed.

Why didn’t the central government stop the Kashmir exodus?

The central government’s failure to prevent the exodus stemmed from multiple factors: political instability (V.P. Singh’s minority government lasted only 11 months), inadequate intelligence about the scale of militant infiltration, compromised local security forces, and a lack of political will to confront terrorism decisively. The BJP’s external support came without demands for minority protection. National Conference-Congress politics in Kashmir prioritised electoral calculations over security. Most critically, Kashmiri Pandits lacked electoral significance, making their protection politically optional rather than mandatory. The exodus revealed how minority rights become negotiable when communities lack political leverage.

What was the Ayodhya movement’s connection to Kashmir policy?

The Ayodhya Ram Mandir movement and the Kashmir policy were directly connected through political prioritisation. L.K. Advani’s Rath Yatra (September-October 1990) mobilised millions and offered the BJP massive electoral returns across northern India. When Lalu Prasad Yadav arrested Advani, the BJP immediately withdrew support from V.P. Singh’s government. This political leverage was available for Kashmir, but was never deployed for Kashmiri Pandit protection. The Ayodhya mobilisation promised Hindu vote consolidation across multiple states; Kashmir offered only moral responsibility for an electorally insignificant minority. This strategic choice defined the BJP’s approach during the exodus.

Can Kashmiri Pandits return to the Kashmir Valley?

Kashmiri Pandit return remains largely unrealised 35 years after the exodus. While some government schemes exist, including PM package employees and rehabilitation programs, actual return has been minimal due to ongoing security concerns, lack of economic opportunities, absence of political will, and emotional trauma from displacement. Most Kashmiri Pandit refugees now live in Jammu, Delhi, and other Indian cities, with younger generations born outside Kashmir. True rehabilitation would require comprehensive security guarantees, economic reconstruction, justice for past violence, and political commitment that has historically been absent. The community remains politically useful as a symbol but is inadequately supported for actual return.

What is the current status of Kashmiri Pandit rehabilitation?

Kashmiri Pandit rehabilitation efforts remain inadequate and fragmented. Some families receive small monthly compensation. The government employs some youth under special packages in Kashmir, though many face security threats. Migrant camps in Jammu still house displaced families in difficult conditions. Property loss compensation is incomplete, and many ancestral homes have been occupied or destroyed. Political rhetoric about Kashmiri Pandits continues across parties, but substantive policy action on rehabilitation, justice, and return has been limited. The Article 370 abrogation in 2019 was claimed to enable return, but ground realities show minimal actual repatriation. The community remains caught between symbolic political importance and practical policy neglect.

How did the 1986 communal riots affect Kashmir?

The 1986 Kashmir communal tensions under Ghulam Mohammad Shah’s government normalised religious polarisation in public discourse. This period saw organised communal mobilisation, inflammatory speeches, and the legitimisation of religious identity as a political weapon. The social fabric that had previously allowed Hindu-Muslim coexistence began fraying systematically. Religious leaders gained political influence, and the secular nature of Kashmiri politics eroded. This communal polarisation in the mid-1980s created the ideological groundwork that militants later exploited. Understanding the 1986 turning point is crucial because it shows that Kashmir’s radicalization was a gradual process enabled by political choices, not a sudden phenomenon.