Introduction: A Statement That Reopened Old Wounds

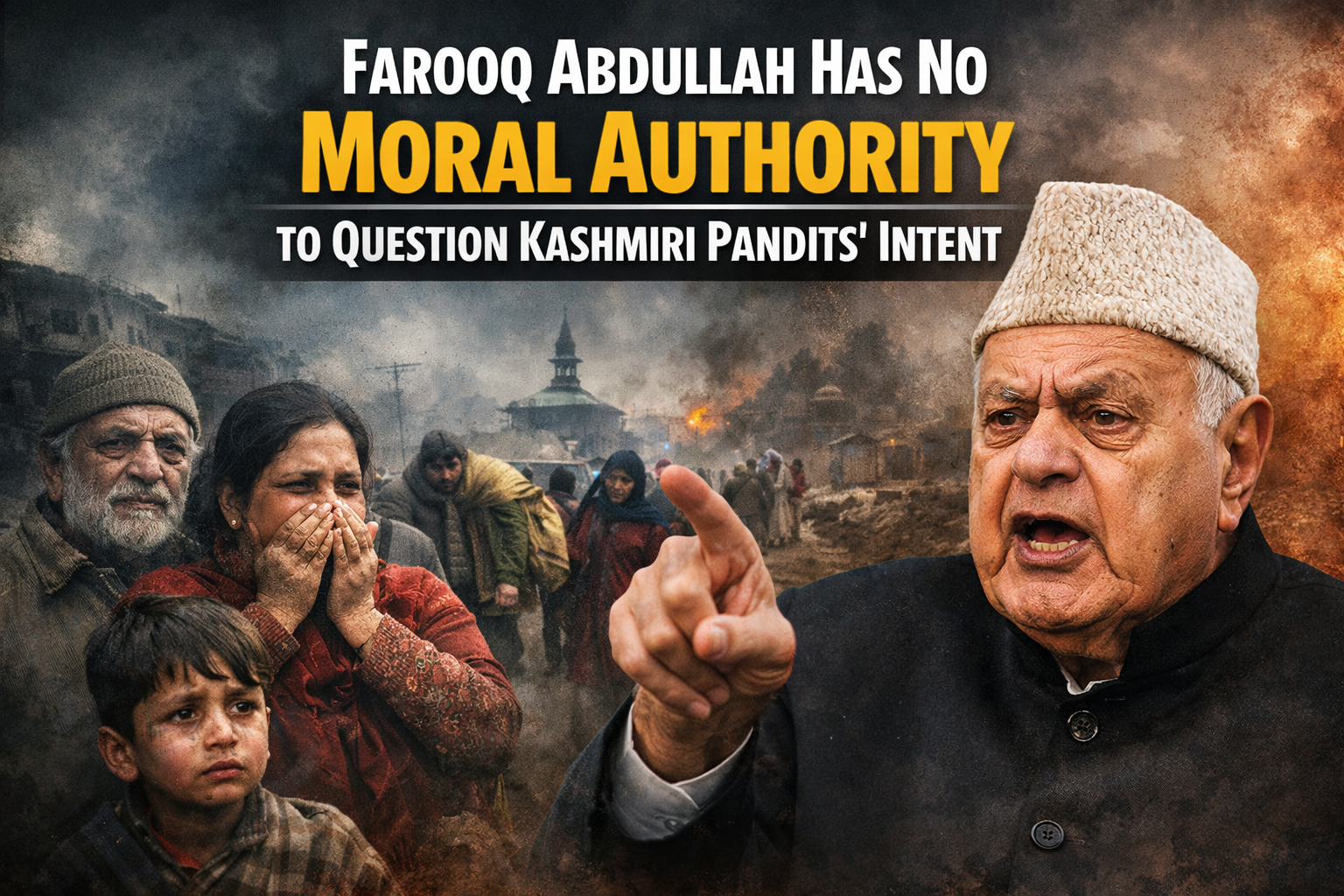

On January 19, 2026, Dr Farooq Abdullah made a statement that shocked the Kashmiri Pandit community. The National Conference President said displaced Pandits are “welcome” to return. However, he doubted they would ever come back permanently.

This was the 36th anniversary of “Holocaust Day” for Kashmiri Pandits. The timing could not have been worse. Moreover, Abdullah suggested the community had built new lives elsewhere. He implied they might only return as tourists.

To outsiders, this might sound like a realistic observation. After all, 36 years have passed since the exodus. Nevertheless, for survivors of the 1990 exodus, his words cut deep. They represent something more troubling than insensitivity. They amount to historical revisionism.

Furthermore, his statement tries to reframe a violent ethnic cleansing as a lifestyle choice. Before Farooq Abdullah questions whether Kashmiri Pandits want to return, we must examine his own actions. Specifically, we need to scrutinise what he did when the community needed protection most.

When Leadership Vanished, So Did Moral Legitimacy

The Social Contract Betrayed

Political authority rests on a simple agreement. The state provides security and protection. In return, citizens offer allegiance and participation. However, in January 1990, the state of Jammu and Kashmir completely broke this contract.

Chief Minister Farooq Abdullah led that state. Critics argue that he destroyed any moral authority to speak about Kashmiri Pandits. His actions during winter 1989-1990 prove this point. Consequently, his recent comments ring hollow.

The timeline reveals a damning truth. Abdullah chose political self-preservation over constitutional duty. Instead of protecting all citizens, he walked away. This decision would haunt an entire community for decades.

The Midnight Resignation: January 18, 1990

The sequence of events matters greatly. On January 18, 1990, Farooq Abdullah faced a political challenge. The central government planned to appoint Jagmohan Malhotra as the new Governor. Abdullah viewed Jagmohan as a personal threat. You can get the full details in the Shadows over the Valley

Therefore, Abdullah made a fateful decision. He resigned as Chief Minister at midnight. However, his resignation was not based on principle. It was not about protecting citizens. Instead, it stemmed from political rivalry and personal animosity.

Abdullah saw Jagmohan as a threat to his power base. Rather than ensuring a smooth transition, he simply left. Meanwhile, the Kashmir Valley was becoming increasingly dangerous. Communal tension was rising. Militant activity was spreading. Targeted violence against minorities was escalating.

Despite all this, Abdullah walked away from his responsibilities. He abandoned the Chief Minister’s office at the worst possible moment. This act of political cowardice would have devastating consequences.

From January 18 to January 19: The Silence That Enabled an Exodus

Twenty-Four Hours of Complete Chaos

The next 24 hours represent a catastrophic failure of governance. From January 18 to January 19, Jammu and Kashmir existed in administrative limbo. There was no Chief Minister in office. The new Governor had not yet taken charge. The state machinery had no clear leadership.

This created a power vacuum. Consequently, radical elements seized the opportunity. The police and security forces lacked clear direction. Furthermore, many officers were already compromised through intimidation. Into this void stepped forces that had been waiting for exactly this moment.

The Night of Terror: January 19, 1990

As darkness fell on January 19, 1990, something horrifying happened. Mosque loudspeakers across Srinagar crackled to life. Similar broadcasts occurred in other Valley towns. However, these were not calls to prayer. Instead, they were direct threats against Kashmiri Pandits.

The slogans echoed through the cold winter night:

“Ralive, Tchalive, ya Galive” (Convert to Islam, Leave Kashmir, or Die)

“Kashmir mein agar rehna hai, Allah-O-Akbar kehna hai” (If you want to stay in Kashmir, you must say Allah-O-Akbar)

“Yahan kya chalega, Nizam-e-Mustafa” (What will rule here? The system of the Prophet)

These were not isolated incidents. They were coordinated attacks. Moreover, they were systematic threats designed to create maximum terror. The broadcasts came from multiple religious institutions across different towns.

Most importantly, they were met with complete official silence.

The Government That Wasn’t There

During these critical hours, the Kashmiri Pandit community desperately needed help. They needed visible police protection. They needed curfews imposed. They needed arrests of those making threats. They needed emergency meetings with community leaders. They needed public statements of reassurance.

Instead, they got nothing. The government machinery had stopped functioning. There was no response whatsoever.

Wajahat Habibullah served as a senior civil servant during this period. He later became India’s Chief Information Commissioner. According to Habibullah, this administrative vacuum was the “latent cause” of panic. The absence of any government presence sent a clear message. Kashmiri Pandits were on their own.

By the time officials tried to react, it was too late. The exodus had already begun. Families packed whatever they could carry. They fled into the night toward Jammu and other parts of India. Behind them, they left centuries of history and civilisation.

The Rubaiya Sayeed Surrender: When Everything Changed

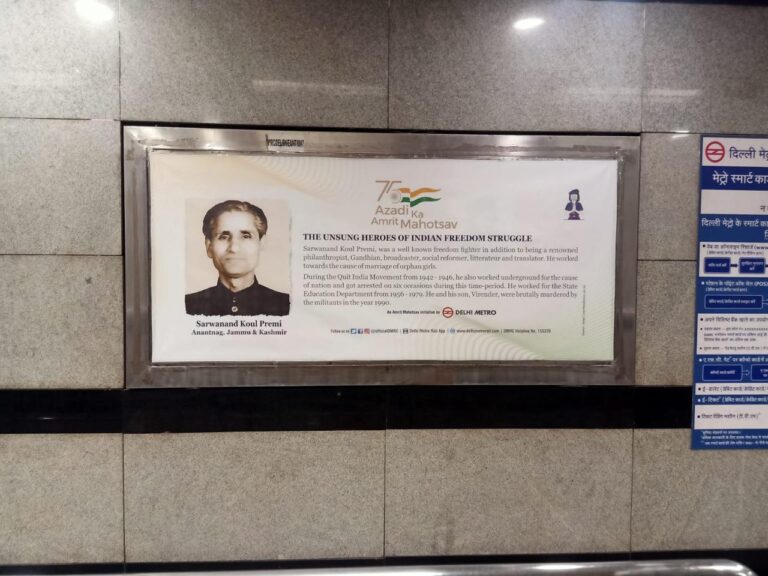

December 8, 1989: The Kidnapping That Changed Kashmir

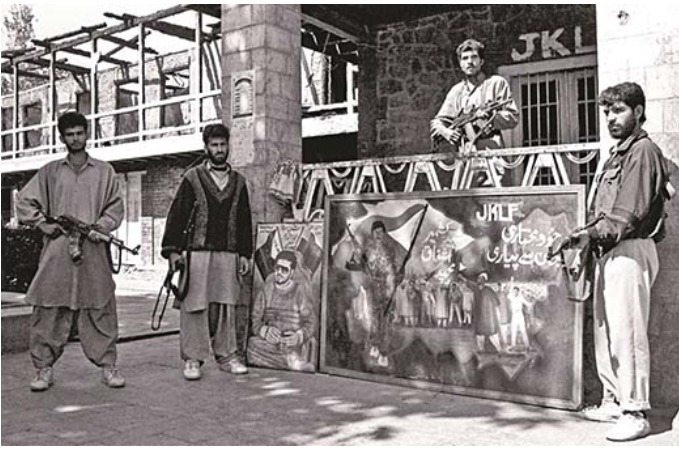

To understand Abdullah’s moral failure, we must go back further. On December 8, 1989, militants kidnapped Rubaiya Sayeed. She was the daughter of Union Home Minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed. The Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) carried out the abduction.

Their demand was simple. They wanted five hardcore JKLF terrorists released. In exchange, they would free Rubaiya Sayeed.

December 13, 1989: A Fatal Capitulation

After five days, the government surrendered completely. Both the state government under Abdullah and the central government agreed. All five militants were released. Rubaiya Sayeed was freed unharmed.

However, the consequences were catastrophic. The released militants included Hamid Sheikh. He later became a prominent militant commander. He was responsible for numerous deadly attacks.

The message was unmistakable. Militancy works. Kidnapping produces results. The Indian state will negotiate with terrorists. Violence pays dividends. This capitulation emboldened militants across Kashmir.

Abdullah’s Failure to Stand on Principle

In later years, Farooq Abdullah claimed he was “pressured” by the central government. He suggested the decision was not entirely his. However, this defence fails on multiple levels.

First, if Abdullah truly believed releasing terrorists would “open the floodgates,” he had a clear duty. He should have resigned immediately in protest. A principled resignation in December 1989 would have preserved his credibility. He could have publicly warned of the consequences.

Instead, Abdullah did something different. He stayed in office and oversaw the release. Then, six weeks later, he resigned anyway. But his resignation was not about principle or public safety. It was about a personal political rivalry with Jagmohan. The contrast could not be more damning.

Second, as Chief Minister, Abdullah understood the ground situation better than anyone. He knew about the precarious position of Pandits. He understood the growth of radical sentiment. He recognised the fragility of communal peace.

If anyone should have sounded alarm bells, it was Abdullah. Instead, he acquiesced silently. Then he abandoned his post when predictable consequences materialised.

The Myth of “No One is Preventing Them”

Reframing Ethnic Cleansing as Personal Choice

In his January 2026 remarks, Farooq Abdullah asked a question. “Who is stopping them? No one is preventing them from returning.” This framing is deeply problematic. It suggests Kashmiri Pandits choose to stay away. It implies their absence is a matter of personal preference.

This rhetoric ignores several critical realities:

- Deep Psychological Trauma: Communities that experience ethnic cleansing do not simply “move on.” The trauma passes through generations. Survivors carry memories of murdered neighbours and desecrated temples. They remember the terror of midnight flight. Their children grow up hearing these stories.

Therefore, the question is not about physical barriers. It is about trust. Can Pandits trust the state to protect them if they return?

- Ongoing Security Concerns: The situation in Kashmir has evolved since 1990. Nevertheless, targeted killings continue sporadically. In 2021-2022, several Pandit government employees were assassinated. Migrant workers were also killed. Each incident confirms the community’s worst fears. Each validates their decision to stay away.

- Complete Loss of Property and Livelihood: Many Pandits lost everything in 1990. They lost homes, businesses, and agricultural land. They lost professional practices built over generations.

The idea that they can simply “return” ignores economic reality. Their assets were destroyed or occupied by others. Many properties have deteriorated beyond repair. There has been no comprehensive restitution program.

- Shattered Trust: Most fundamentally, Abdullah’s question ignores a basic truth. Trust, once broken, cannot be rebuilt with mere words. The community trusted the state in 1990. The state failed catastrophically.

Why should they trust assurances now? Particularly when those assurances come from the very leadership that failed them before?

The “Better Lives Elsewhere” Narrative

Abdullah suggested that Pandits have “built new lives” elsewhere. He implied they might only return as “tourists.” This characterisation is particularly offensive.

Yes, the community has rebuilt their lives. Through extraordinary resilience and hard work, they established themselves in new cities. They found new professions and built new social networks. Their children got educated, married, and started careers.

However, this was not an aspirational migration. This was not a search for better opportunities. This was survival. These were refugees rebuilding from nothing because they had no choice.

To characterise their absence as a voluntary preference is fundamentally wrong. They did not leave seeking “better education and employment.” They left because neighbours were being murdered. They left because the state had abandoned them.

The Pattern of Denial and Minimisation

A Consistent Refusal to Accept Responsibility

Farooq Abdullah’s recent comments are not isolated. They are part of a broader pattern. For more than three decades, the National Conference has denied and minimised the exodus.

Over the years, National Conference leaders have:

Questioned the number of Pandits who were killed

Suggested that casualty figures are “exaggerated”.

Downplayed the religious nature of the targeting

Claimed violence affected all communities equally

Emphasised Muslim suffering while ignoring Pandit suffering

Blocked rehabilitation efforts by adding political conditions

Suggested Pandits were “used” by the government for political purposes

This pattern reveals a fundamental problem. Acknowledging ethnic cleansing happened on your watch requires moral accountability. That accountability has been conspicuously absent.

What Genuine Reconciliation Would Require

Beyond Empty Words and False Welcomes

If Farooq Abdullah truly wanted Kashmiri Pandits to return, his approach would be different. Genuine reconciliation would require several concrete steps:

- Full Historical Acknowledgement: An unambiguous public statement is necessary. The Kashmiri Pandit community was subjected to targeted violence. This violence amounted to ethnic cleansing. Furthermore, state government failures in 1989-1990 directly contributed to this catastrophe.

- Personal Accountability: Abdullah himself must acknowledge his failures. His midnight resignation represented a betrayal of leadership. It was a violation of his constitutional duty to all citizens of Jammu and Kashmir.

- Concrete Security Guarantees: Verbal assurances are not enough. The state needs demonstrable security arrangements with independent oversight. This might include dedicated police stations and community liaison officers. It requires rapid-response protocols. It demands harsh penalties for hate speech or violence.

- Comprehensive Restitution: A properly funded program is essential. It must restore property where possible. It should provide compensation where restoration is impossible. It needs to create economic opportunities for returning families.

- Educational Curriculum Reform: Kashmir’s schools must teach honest history. The next generation should understand what happened. They need to know why it must never happen again.

- Justice and Truth: Many perpetrators may never be held accountable. Too much time has passed. Nevertheless, there should be a truth and reconciliation process. It should document crimes and, where possible, identify perpetrators. It must provide closure to victims’ families.

None of these elements exists in Abdullah’s current approach. Instead, he offers only sceptical observations about the return. These sound more like rationalisation than reconciliation.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Abandonment

Farooq Abdullah’s January 2026 comments about Kashmiri Pandits reveal more than insensitivity. They expose an unrepentant mindset. This mindset has characterised the National Conference for over three decades.

The central historical truth is inescapable. Kashmiri Pandits did not choose to leave. They did not choose to remain in exile. Their absence stands as a permanent monument. It testifies to failed political leadership in 1990.

That leadership faced a choice between political self-interest and constitutional duty. It chose to walk away. For such a leader to now question victims’ intent to return is deeply troubling. It represents an ongoing abdication of responsibility.

Dr Abdullah asks, “Who is stopping them?” The answer is clear. The legacy of his failures in 1990 continues to hold them back. The memory of the state that vanished stops them. The absence of accountability, justice, and genuine security guarantees stops them.

Before Farooq Abdullah offers more scepticism about Kashmiri Pandits returning, he owes them something. He owes the community and history a full accounting. He must explain the silence of January 18-19, 1990. He must explain why he chose that moment to resign. He must acknowledge that his actions created a power vacuum. That vacuum allowed radical elements to seize control.

Until such accountability comes, his observations mean nothing. They are self-justifications from someone unwilling to confront their role. His role in one of India’s darkest episodes of communal violence cannot be erased.

The Kashmiri Pandits deserve better than scepticism. They deserve truth, acknowledgement, accountability, and genuine reconciliation. Anything less is simply another chapter in their betrayal. A betrayal by those who swore to protect them.

The wounds of 1990 will not heal through time alone. They will heal only when those responsible speak the truth about what happened and why. Thirty-six years later, the Kashmiri Pandit community is still waiting.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What did Farooq Abdullah say about Kashmiri Pandits in 2026?

A: On January 19, 2026, Farooq Abdullah stated that while Kashmiri Pandits are welcome to return, he doubts they will come back permanently. He suggested they had built new lives elsewhere and might only visit as tourists.

Q: When did Farooq Abdullah resign as Chief Minister?

A: Farooq Abdullah resigned as Chief Minister on January 18, 1990, at midnight. This was just hours before the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits began on January 19, 1990.

Q: What happened on January 19, 1990?

A: On January 19, 1990, mosque loudspeakers across Kashmir broadcast threats against Kashmiri Pandits. The slogans included “Raliv, Tchaliv, ya Galiv” (Convert, Leave, or Die). This triggered the mass exodus of the community.

Q: What was the Rubaiya Sayeed kidnapping?

A: On December 8, 1989, militants kidnapped Rubaiya Sayeed, daughter of Union Home Minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed. The government released five hardcore terrorists in exchange for her freedom on December 13, 1989. This capitulation emboldened militants across Kashmir.

Q: How many Kashmiri Pandits were displaced in 1990?

A: Estimates suggest that between 300,000 and 400,000 Kashmiri Pandits were forced to flee the Kashmir Valley during the 1990 exodus. Most have never returned permanently.