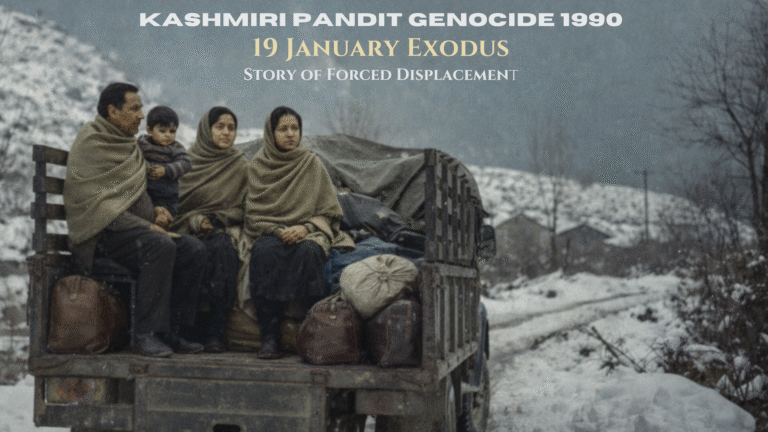

Public memory often prefers events that can be dated, explained, and concluded. In that sense, the Kashmiri Pandit exodus sits uncomfortably within our collective understanding, because it resists such neat treatment. It is usually described as something that happened at a particular moment, when in fact it was the result of a gradual deterioration that neither announced itself nor prompted a timely correction.

What deserves closer attention is not only the act of departure, but the conditions that the departed appear reasonable, even unavoidable, to those who had lived in the valley for generations. Long before homes were locked and neighbourhoods emptied, something quieter had begun to erode. Assurance weakened. Institutional response became uncertain. Familiar routines lost their sense of permanence.

These changes rarely attract notice at the time. They do not arrive as orders or declarations. They register instead as hesitations, delays, and the gradual withdrawal of confidence in a protection taken for granted until it is no longer dependable. When such conditions persist, fear does not need to be dramatic to be decisive.

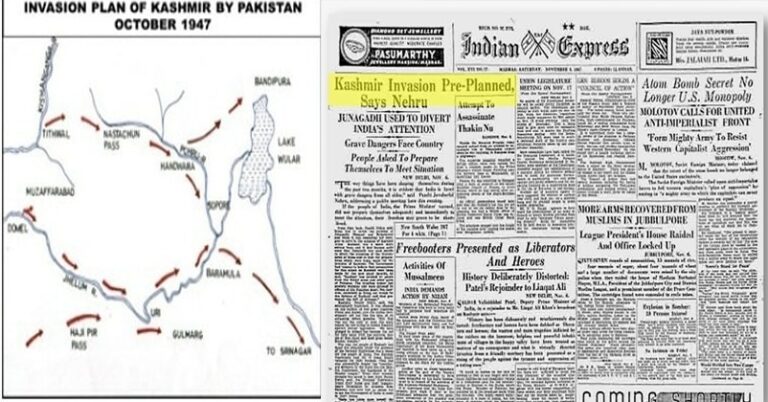

Much of what is written today focuses on consequences rather than causes, on outcomes rather than processes. This is understandable, but incomplete. A society does not wake up one morning to discover that a community has vanished. It reaches that point through a sequence of failures, each small enough to be explained away, and together large enough to alter destiny.

There is also a tendency, over time, to speak of displacement as though it were an episode that concluded once physical movement occurred. In reality, displacement continues in memory, in fractured inheritance, and in the slow fading of context. When the reasons behind an exodus are not carefully examined, the event itself begins to lose definition and, eventually, moral clarity.

This narrowing of memory has consequences. It makes specific questions appear settled when they are not. It allows responsibility to dissolve into generalisation. Above all, it encourages a belief that what happened was inevitable, rather than the result of identifiable decisions, absences, and silences.

The purpose of revisiting such questions is not to reopen wounds nor to seek dramatic affirmation. It is to resist the quiet erosion of truth that accompanies the passage of time. History, when left unattended, does not merely fade. It reshapes itself into something more convenient.

There are aspects of the Kashmiri Pandit exodus that cannot be responsibly addressed in a short reflection without doing violence to their complexity. They require patience, chronological honesty, and a willingness to sit with discomfort rather than resolve it quickly.

Those aspects form the substance of Shadows Over the Valley.