Tourism in Kashmir took the spotlight on September 29, 2025, when the administration announced the reopening of 12 destinations shut since the April 22 Pahalgam terror attack.

The list included Aru Valley, Rafting Point Yanner, Akkad Park, Padshahi Park, and Kaman Post in the Kashmir division, along with Dagan Top in Ramban, Dhaggar in Kathua, Shiv Cave in Salal, and Reasi in Jammu.

Officials framed it as a boost for the Valley’s resilience and economy. But the deeper question remains: can tourism alone define normalcy when the long-awaited return of Kashmiri Pandits is still pending?

The Pahalgam Attack: A Trigger and a Reminder

On April 22, 2025, militants targeted tourists in Baisaran Valley near Pahalgam, killing 26 civilians and injuring several others. The attackers reportedly used modern rifles and created chaos among unarmed visitors, striking at the heart of Kashmir’s tourism-dependent economy.

The government responded by shutting down 48 out of 87 authorised tourist resorts in the Valley, citing security concerns. Bookings plummeted, guides lost work, and the fragile tourism sector faced a setback similar to the lockdowns of the 1990s.

The reopening of 12 spots is being positioned as a recovery. Yet it also underlines a cycle that has become familiar in Kashmir: attack, closure, reopening, repeat. It is a cycle that offers optics of normalcy but rarely addresses the deeper fractures in the region’s social and political fabric.

The Politics of Normalcy: Tourism as a Symbol

Tourism in Kashmir is not just an economic activity. It has always been political. Each tourist arrival is counted as proof of peace. Each reopening is hailed as evidence that the Valley is “back to normal.”

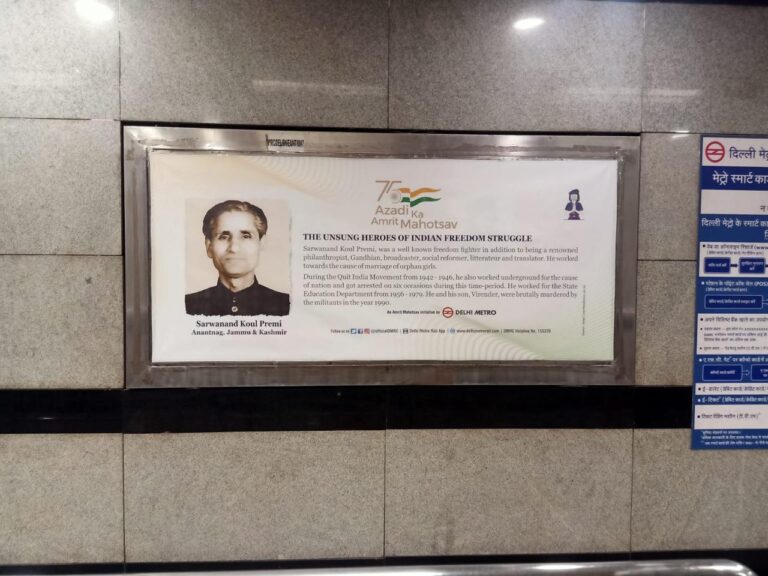

But this framing is selective. By celebrating the return of tourists, authorities shift focus away from the fact that an entire community remains absent from the land of its ancestors. For Kashmiri Pandits, the displacement of 1990 was not temporary. It has stretched into a 35-year exile, marked by broken promises and missed opportunities.

The truth is simple. A Kashmir where Pandits still live as refugees in their own country cannot be considered normal, no matter how many tourists visit Gulmarg or Sonamarg.

BJP’s Promises: A Decade of Assurances Without Delivery

Since 2014, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has continually pledged to resettle Pandits in the Valley. Its 2014 election manifesto stated that the return of Pandits was a national priority. The 2019 manifesto reiterated the same pledge, positioning their resettlement as part of the broader narrative of integration following the abrogation of Article 370.

Yet, six years after the revocation of Article 370 in 2019, no comprehensive resettlement plan has been implemented. Kashmiri Pandits remain scattered across Delhi, Jammu, and other cities, many living in transit accommodations or struggling with the weight of exile.

The gap between promises and delivery has widened. Symbolic reopenings of tourist spots may create headlines, but they cannot mask the fact that the political assurances given to Pandits remain unfulfilled.

Normalcy Defined by Absence, Not Presence

The reopening of 12 tourist sites raises a deeper question: what exactly do we mean by “normalcy”?

- Is it tourists sipping tea in Aru Valley or Pandits performing puja in their ancestral temples?

- Is it rafting in Pahalgam or the children of Pandits studying in schools built by their ancestors?

- Is it hotel bookings returning to normal, or the return of families who once kept the Valley’s pluralistic culture alive?

Normalcy cannot be measured in hotel occupancy rates or the number of visitors trekking in the Lidder Valley. It must be measured in terms of whether displaced communities can reclaim their homes without fear of reprisal. Until then, the Valley remains incomplete.

The Economic vs. Human Dimension

Tourism is essential for Kashmir’s economy. It contributes nearly 7 % to the GDP of Jammu and Kashmir and provides livelihoods to thousands. When spots reopen, guides, drivers, and artisans breathe a little easier.

But the human cost of displacement is not reflected in GDP figures. For Kashmiri Pandits, exile has meant the loss of property, culture, language ties, and spiritual heritage. Their absence also erodes the Valley’s historic identity as a land of shared traditions.

By prioritising tourism optics over rehabilitation, policymakers risk treating Pandit’s return as secondary. That is a dangerous message: it suggests that economic recovery is more important than social justice.

Security for Tourists vs. Security for Residents

The government deploys heavy security for tourists. Popular sites are monitored; routes are guarded, and new checkpoints are established. This protection is essential, but it exposes a contradiction.

If the state can create layered security systems for short-term visitors, why is it unable to make permanent security arrangements for Pandit families? The fear is not theoretical. Targeted killings of minority community members in the Valley have occurred even in recent years. Without addressing this reality, resettlement remains a distant dream.

Why Pandit Rehabilitation Matters to Kashmir’s Future

The return of Kashmiri Pandits is not just about justice for one community. It is about the Valley’s future.

- Pluralism: Their return would restore the multicultural fabric of Kashmir that existed before militancy tore it apart.

- Trust Building: Rehabilitation would demonstrate that the Valley is safe for all, not just tourists.

- Political Integrity: Honouring promises strengthens democracy and restores faith in governance.

- Long-Term Stability: Pandit’s return will mark the end of exile politics, laying the groundwork for reconciliation.

Without their return, Kashmir risks being seen as a region that welcomes outsiders for vacations but cannot protect its own people.

The Hard Questions Moving Forward

- What concrete steps has the government taken to implement its manifesto promises on Pandit rehabilitation?

- Why is there no clear timeline or roadmap for their return?

- Are authorities using tourist reopenings to project stability while avoiding more challenging political tasks?

- How can normalcy be celebrated when thousands of displaced families still wait for justice?

Towards Real Normalcy: Beyond Symbolism

Reopening tourist spots is essential, but it is symbolic. Absolute normalcy demands structural change. A roadmap for Pandit rehabilitation will include:

- Safe Housing Projects: Not transit camps, but integration into regular neighbourhoods.

- Community security mechanisms: Local policing and intelligence coordination to prevent targeted violence.

- Economic Incentives: Job creation and property restoration to make the return sustainable.

- Cultural Revival: Restoration of temples and cultural sites to reconnect displaced communities to their heritage.

Conclusion:

The reopening of 12 tourist destinations in Kashmir may be framed as a victory for resilience, but it should not blind us to the more profound truth. Normalcy is not when tourists raft in Pahalgam. Normalcy will be when Kashmiri Pandits light diyas in their ancestral homes without fear.

The BJP, which pledged this return in both 2014 and 2019 manifestos, carries the responsibility to deliver. Until those promises are honoured, every reopening risks being remembered as an exercise in optics rather than a milestone of peace.

Kashmir’s beauty will always draw visitors. But its soul will remain incomplete until the community that was driven out 35 years ago is finally welcomed back with dignity and security. That will be the real test of whether the Valley has truly returned to normal.