Kashmiri Pandits. The name itself paints a picture – a people with a history stretching back thousands of years, deeply connected to the land of Kashmir. Kashmiri Pandits have known victories and losses, their rich culture blooming like the valley’s roses and weathering tough times like the mountain peaks.

Imagine families living in the same place for ages, hearing stories of gods and goddesses whispered in ancient temples. That’s the heritage carried by the Pandits, passed down through generations. But their journey hasn’t been easy. They’ve seen their land change hands, and their beliefs challenged, but they held their heads high, adapting and keeping their spirit alive.

Then came a dark chapter – a forced exodus that tore them away from their homes, scattering them like seeds in the wind. Leaving everything behind, fear gripped their hearts, a pain that still lingers even today.

But the Pandits are not just defined by their suffering. They’re the heroes who rebuilt their lives, brick by brick, carrying their traditions in makeshift temples and stories shared amongst loved ones. They’re the children who grew up with tales of a lost paradise, longing for a home they’ve never known.

Let’s explore the history of Kashmiri Pandits

Who are Kashmiri pandits

Kashmiri Pandits are the aboriginal people of Kashmir. Kashmiri Pandits, are a group of people with a unique history and culture deeply woven into the fabric of Kashmir. But their journey hasn’t been easy. It’s filled with ups and downs, triumphs and tragedies, that showcase their incredible spirit.

The forefathers of the Kashmiri Pandits traversed northward from the ancient banks of the Sarasvati River, establishing their abode in the Kashmir Valley over five millennia ago.

Emergence of Shaivism:

The 1st millennium witnessed Kashmir blossom into a prominent centre of Hinduism. Shaivism, a major Hindu sect worshipping Lord Shiva, took root and flourished during this era. Renowned philosophers like Adi Shankaracharya played a pivotal role in its revival, leaving an enduring legacy of profound teachings and monastic centres.

In the initial half of the 1st millennium, the Kashmir region evolved into a pivotal centre for Hinduism and subsequently, under the reigns of the Mauryas and Kushans, for Buddhism. The ascent of Shaivism during the ninth century, amid the Karkota Dynasty’s rule, marked a significant indigenous development. Flourishing through seven centuries of Hindu dominance, it continued under the Utpala and Lohara dynasties, reaching its culmination in the mid-14th century.

Over the centuries, Kashmiri Shaivism evolved into a distinctive school of thought within the broader Shaiva tradition, renowned for its unique philosophical doctrines, mystical practices, and devotional poetry. Scholars such as Abhinav Gupta, a 10th-century philosopher, played a pivotal role in blending tantric practices with profound philosophical insights, contributing significantly to the development of Kashmiri Shaivism.

Spread of Islam

The spread of Islam in Kashmir gained momentum from the 14th century onward. The region witnessed a series of invasions and migrations that contributed to the propagation of Islam. Muslim rulers and dynasties, such as the Shah Mir dynasty and later the Chak dynasty, played a crucial role in the establishment of as a dominant religious and political force.

While the dawn of the Shah Mir dynasty marked a new chapter, it marked a shadow on the Kashmiri Pandit community, facing religious conversions, religious killings, persecutions and measures like the ‘jizya’ tax, and the desecration of their cherished temples. The destruction of the Martand Sun Temple is a stark reminder of the violence that was inflicted on the Hindu community during this period.

For more information read ” Uprooted and Forlorn”: The tale of Kashmiri Pandits in exile

Unravelling the Tragic Saga of Forced Migration

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the serene valleys of Kashmir became the backdrop for a heart-wrenching tale—the mass exodus of the Kashmiri Pandit community. A convergence of political turmoil, religious intolerance, and escalating violence propelled thousands to abandon their ancestral homes, leaving an indelible mark on the community’s identity.

As extremism gained momentum, the Hindu faith of Kashmiri Pandits became a target. A rising wave of religious intolerance, coupled with targeted persecution, created an atmosphere of fear, where the safety of the community was compromised.

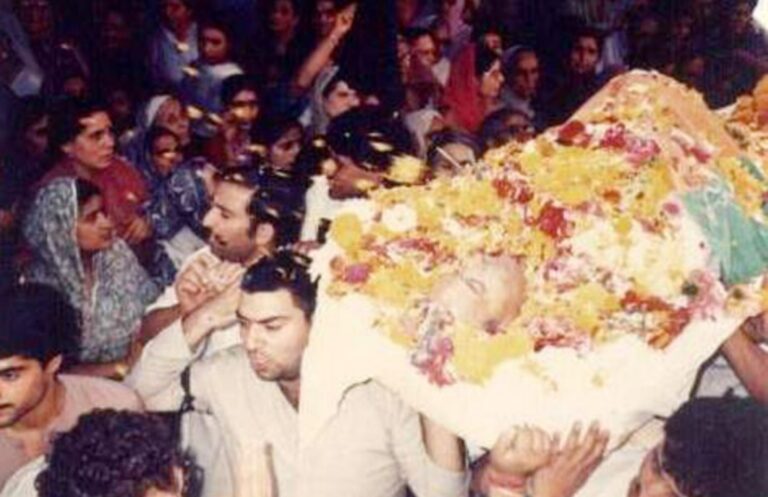

A Dark Turning Point: Targeted Killings and the Flight of Kashmiri Pandits

From 1989 to 1990, a series of horrific events triggered a mass exodus of Kashmiri Pandits from their ancestral home in the Kashmir Valley. This article highlights some of the key incidents that fueled fear and forced displacement:

September 14, 1989: The assassination of prominent Kashmiri Pandit leader Tika Lal Taploo marked the start of targeted attacks on the community. This grim event foreshadowed the exodus to come.

November 4, 1989: The brutal killing of retired judge Justice Neelkanth Ganjoo, who had sentenced a Kashmiri separatist leader to death, sent shockwaves through the community and heightened anxieties.

February 13, 1990: The kidnapping and murder of well-known Door Darshan broadcaster Lassa Kaul further amplified the atmosphere of fear and insecurity among Kashmiri Pandits.

April 30, 1990: The tragic killing of renowned poet Sarvanand Kaul and his son, followed by their public display, epitomized the escalating violence and terror faced by the community.

These targeted killings, coupled with a pervasive climate of violence and intimidation, forced a large number of Kashmiri Pandits to flee their homes and seek refuge elsewhere in India.

On January 19th, 1990, during a period of heightened tensions in Kashmir, a large number of Kashmiri Pandits, a minority Hindu community, were forced to flee the Kashmir Valley due to threats and violence.

This mass exodus significantly altered the demographic and cultural makeup of the Kashmir Valley, leaving a permanent scar on the region’s history.

Lost Home: Imagine leaving the place where your family has lived for generations, the streets you played on, and the whispers of history in the air. That’s what happened to Kashmiri Pandits. Their villages, now deserted, hold the echoes of a vibrant past.

Lost Culture: More than just houses, they left behind a way of life. Festivals, traditions, and even everyday routines had evolved along with them in Kashmir. In their new surroundings, they strive to keep their culture alive, but it’s like a garden uprooted, struggling to bloom again.

The trauma of forced migration left enduring psychological scars. The mental health of individuals bore the brunt of the exodus, with the echoes of violence and upheaval haunting the collective psyche of the community.

The dispersion of the community posed challenges in maintaining a cohesive identity. The Kashmiri Pandits, now scattered across different regions, grappled with the task of preserving their cultural continuity in the face of geographical and societal diversity.

FAQs on Kashmiri Pandits

Who are Kashmiri Pandits?

Kashmiri Pandits are a Hindu community with a rich history and deep connection to the Kashmir Valley.

What happened to them?

They faced a forced exodus in the 1990s due to violence and insecurity, leaving their homes and scattering across India.

How are they coping?

Despite the challenges, they have rebuilt their lives, preserving their traditions and culture.

What is their future?

Many hopes for a safe return to their homeland, while others focus on contributing to society.

Demand justice for the Kashmiri Pandits: Raise your voice and support initiatives seeking accountability for the atrocities they faced.